People connect to nature best when it’s with their head and their heart. That’s what led students at Upper Arlington High School in Columbus, OH, to create a self-guided Meditation Nature Trail at a local ecology center.

Beginning in the 2008-09 school year, students teamed up with Capitol Square Rotary Club to design and construct the trail. The students took charge investigating local ecosystems, determining a route and station locations, developing themes, and conducting an online survey to better understand how the local community best connects to nature.

Beginning in the 2008-09 school year, students teamed up with Capitol Square Rotary Club to design and construct the trail. The students took charge investigating local ecosystems, determining a route and station locations, developing themes, and conducting an online survey to better understand how the local community best connects to nature.

They set up the trail at Shepherd’s Corner, a 160-acre ecology center of the Dominican Sisters of Peace located in Blacklick, Ohio. Each station sign includes a fact for the mind, a reflection for the heart, and an activity for the entire being.

Originally designed as a five-week inquiry-based project, the students continued to volunteer their time for the next year and a half. “At first, I just got involved because I needed some service hours. But then I really began to feel connected to the place – and I saw I could make a difference and do something positive to help people and the environment,” said Rose Mantel, an Upper Arlington High School student.

The students enjoyed seeing their ideas come to life in the trail stations. After the completion of that project, they decided to undertake a final project to tie everything together and create a more holistic learning experience for the trail visitors.

With the help of a PLT GreenWorks! grant, students developed and installed the trail’s final station during the 2009-10 school year. This “Web of Life” station, based on PLT Activity 45, culminates all the previous stations’ themes and gets people to think about nature’s countless connections.

Interpreting PLT’s “Web of Life” Activity

In PLT’s “web of life” activity, students conduct research and simulate a food web to discover the many ways that plants and animals are connected. Students decided to bring this activity to a new level. They took on the challenge of interpreting the activity in a way that would work for a permanent structure.

At the Web of Life trail station that the high school students designed, participants learn about and assume the role of a local native species. The physical web provides an opportunity to reflect on the concepts of interconnectedness in nature and effects of losing species.

The 14ft diameter web is composed of nine posts and a sloped cable, enabling people of various ages and heights to reach it. Forty-five removable signs hang on the web, each representing a local native species.

The 14ft diameter web is composed of nine posts and a sloped cable, enabling people of various ages and heights to reach it. Forty-five removable signs hang on the web, each representing a local native species.

Individuals can read, remove, relocate, and wear the signs as they explore relationships among species. As individuals tug on the rope, they see how one action can affect multiple areas of the web.

A lot went into the planning process for this station. Many hours were spent at Home Depot, asking questions, deciding construction materials, and evaluating costs. They built a scale mock-up of a web section and species signs. They refined their design several times after presenting their ideas to Shepherd’s Corner staff.

“Working on the Web of Life made me realize how many decisions and small details go into the making of a large-scale project. It was both challenging and rewarding to design something that will appeal to people of all ages and backgrounds,” said Julie Laudick, one of the students who worked on the project.

The Web has several layers of education to it, with various ways it can be used by different age groups. It provides for multiple learning modes, so the educational activity can be memorable for as many youth as possible. When students use the Web, their questions and discussion are thought-provoking.

Debuting the Web of Life

In July 2010, students hosted summer campers (age 9-12) in the first official use of the Web. They met with the local newspaper’s photographer and were interviewed individually by the reporter over the phone.

Watching students experience his work, Gaven McDaniel said, “I really hope that even at such a young age, they begin to understand why they need to watch what they do, because what we do impacts not only ourselves, but everything else that lives around us,” he said. “It might be a stretch, but hopefully they can start making changes in their own lives.”

During the summer, high school students continued to refine how to conduct the activity. Shepherd’s Corner staff use the web with youth groups, and families in the local community visit the trail with their children and engage with the web on their own.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

PLT’s GreenWorks! grants, with their focus on education and student leadership, ensured that the project was student-led and incorporated opportunities for environmental education. To that end, this project was an incredible success, but it did not, however, go without its challenges.

Design challenges

There were plenty of glitches along the way with the design – engineering challenges, not having the correct materials in stock, ground too wet for installation, winter weather too cold for staining, etc. Each of these presented a “real life” opportunity to problem solve. Often, these troubles lead to improved design and implementation.

There were plenty of glitches along the way with the design – engineering challenges, not having the correct materials in stock, ground too wet for installation, winter weather too cold for staining, etc. Each of these presented a “real life” opportunity to problem solve. Often, these troubles lead to improved design and implementation.

Timing

Perhaps the only significant difficulty was timing. The plan was to complete the project in late spring, but the naturally busy ebb and flow of a high school senior’s life was not factored into the original timeline! Beyond graduation and into the summer, the group worked to complete the project in late July.

Planning

In terms of process and education, students were surprised to learn how much planning is involved in a project such as this one. These skills will undoubtedly transfer into future service activities, projects, events – and careers!

Building relationships

Students also established strong and positive working relationships. They worked with Shepherd’s Corner, taking responsibility to complete pieces of the project independently. They built a partnership with Capitol Square Rotary Club and involved 20 of their fellow students.

A new appreciation for their local environment

Students have commented what a deeper, richer respect they have for their local environment. They were dedicated in their research to learn and teach others about nearly 50 local native species. And, perhaps most importantly, they learned to teach others to appreciate the environment around them.

Keys to Success

Community organizations

Community organizations provide adult mentors and opportunities for youth to interact with adults in a coached, safe, real-world environment.

For this project, specific adult skills were available to provide guidance in different situations: an architect and engineer to help with design, an education director/teacher to guide the local species research and educational programming, a naturalist to teach, a farmer “Mr. Fix-it” who had many tools and skills to help us construct.

Students also took some of their design challenges home and enrolled parents or older siblings to help them problem solve.

Start with a small project first

It’s helpful to grow a GreenWorks! project out of another, smaller project. In this case, the GreenWorks! project grew from a previous year’s work with students. They helped create the initial design for the trail in 2008. Wanting to see their vision through to completion, two returning students recruited and lead others in implementing a project of their own. Adults can’t manufacture or demand this commitment; it must grow on its own from within a small committed group of youth – over time.

Commitment to service

It’s helpful for the schools, programs, and organizations involved to have a commitment to service. Upper Arlington High School requires its students to complete service learning hours and a (research or service) project in order to graduate.

Students also helped raise funds for this project, through community booths and bake sales, as well as gathering in-kind donations from their school and parents.

They also gave two public presentations – to the Rotary Club and at a PLT statewide conference. This gave them positive feedback during a long-term project.

Keep in contact with state PLT coordinator

It is rewarding to keep in close contact with your state’s PLT coordinator. This grant was special in the way it engaged students with PLT activities, the Ohio PLT State Coordinator, and other PLT leaders, facilitators, and teachers from across the state.

We invited the Ohio PLT State Coordinator, Sue Wintering, to our Rotary meeting, shared our project with her at different points in design/construction, and invited her to the debut of the educational activity at the Web. It was meaningful and helpful to have this connection and feedback.

Student commitment

Ultimately, the biggest key to success in this project was the devotion and commitment of the students. This project wasn’t something they did to finish their Senior service project or to add a line to their resume. This project became an important thread in their lives.

This happened organically– quietly, joyfully, without any planning or preparation. Mentoring relationships grew between Rotarians, Shepherd’s Corner staff, and students. Friendships grew…and education flourished.

Lowcountry Prep, a K-12 school in Pawleys Island, South Carolina, is an example of how a school can use PLT’s GreenSchools investigations to benefit student learning, the environment, and the bottom line.

Lowcountry Prep, a K-12 school in Pawleys Island, South Carolina, is an example of how a school can use PLT’s GreenSchools investigations to benefit student learning, the environment, and the bottom line.  two to four students each, and conducted their research once a week for six weeks. “It was fun to collect data,” recalled then-9th-grader Elizabeth Zieser-Misenheimer. “When we went into classrooms to measure and weigh, other teachers and students would ask us about what we were doing, so that helped build interest.”

two to four students each, and conducted their research once a week for six weeks. “It was fun to collect data,” recalled then-9th-grader Elizabeth Zieser-Misenheimer. “When we went into classrooms to measure and weigh, other teachers and students would ask us about what we were doing, so that helped build interest.” At the Green Team’s recommendation, watt light bulbs were replaced with watt CFLs, and teachers were encouraged to turn the lights off and use day-lighting as much as possible.

At the Green Team’s recommendation, watt light bulbs were replaced with watt CFLs, and teachers were encouraged to turn the lights off and use day-lighting as much as possible.

teachers considering involvement in PLT’s GreenSchools program:

teachers considering involvement in PLT’s GreenSchools program: theme created by ten students from South Tahoe High School who volunteered to create a presentation for the 2010 Project Learning Tree International Coordinator’s Conference in Lake Tahoe, Nevada. Their project summarized a year-long PLT GreenWorks! service-learning project that involved over 1,700 students.

theme created by ten students from South Tahoe High School who volunteered to create a presentation for the 2010 Project Learning Tree International Coordinator’s Conference in Lake Tahoe, Nevada. Their project summarized a year-long PLT GreenWorks! service-learning project that involved over 1,700 students. Lake Tahoe is a world renowned destination, yet many children who grow up there are not connected to the outdoors. Formed in 2008 with the support of the Forest Service, Generation Green of South Lake Tahoe is a club dedicated to environmental stewardship. The club is primarily made up of students who were not previously connected with the outdoors or natural resource professions.

Lake Tahoe is a world renowned destination, yet many children who grow up there are not connected to the outdoors. Formed in 2008 with the support of the Forest Service, Generation Green of South Lake Tahoe is a club dedicated to environmental stewardship. The club is primarily made up of students who were not previously connected with the outdoors or natural resource professions.  After the students received their certificates, they were ready to visit elementary schools in Lake Tahoe Unified School District. The Generation Green students were teamed with experienced natural resource professionals, who are also PLT educators, to teach younger students about trees and forest conservation. Together they ensured that the environmental education programming met the California State Content Standards.

After the students received their certificates, they were ready to visit elementary schools in Lake Tahoe Unified School District. The Generation Green students were teamed with experienced natural resource professionals, who are also PLT educators, to teach younger students about trees and forest conservation. Together they ensured that the environmental education programming met the California State Content Standards. But the work for the Generation Green students did not end with the tree plantings! In the spring of 2010, PLT chose Lake Tahoe as the site for its International Coordinator’s Conference. To showcase their work, ten Generation Green students began a video project on their personal growth and the Angora Fire. Countless hours of work and preparation resulted in a successful one-hour presentation for the general conference assembly, consisting of nearly 150 environmental educators from across the U.S. and Mexico. In addition, the Generation Green students prepared a break-out session on how to create a DVD with students, to share the lessons they learned.

But the work for the Generation Green students did not end with the tree plantings! In the spring of 2010, PLT chose Lake Tahoe as the site for its International Coordinator’s Conference. To showcase their work, ten Generation Green students began a video project on their personal growth and the Angora Fire. Countless hours of work and preparation resulted in a successful one-hour presentation for the general conference assembly, consisting of nearly 150 environmental educators from across the U.S. and Mexico. In addition, the Generation Green students prepared a break-out session on how to create a DVD with students, to share the lessons they learned.  As part of the conference, the Generation Green students led conference attendees on a field trip to assess the survival of the tree seedlings they had planted last year, and they modeled PLT activities, for example Activity 27 “Every Tree for Itself”, as examples of the educational programming they use to facilitate teaching younger students.

As part of the conference, the Generation Green students led conference attendees on a field trip to assess the survival of the tree seedlings they had planted last year, and they modeled PLT activities, for example Activity 27 “Every Tree for Itself”, as examples of the educational programming they use to facilitate teaching younger students.

“Creation to Migration” garden in Athens, Ohio. Students and teachers partnered with Master Gardeners of Athens County and Wayne National Forest to create a learning laboratory on the school grounds.

“Creation to Migration” garden in Athens, Ohio. Students and teachers partnered with Master Gardeners of Athens County and Wayne National Forest to create a learning laboratory on the school grounds. “If you plant it, they will come” was the theme for Sawgrass Springs Environmental Magnet Middle School’s garden in Coral Springs, Florida.

“If you plant it, they will come” was the theme for Sawgrass Springs Environmental Magnet Middle School’s garden in Coral Springs, Florida.

modest fenced garden in front of Gateway Elementary School in Woodland Park, Colorado.

modest fenced garden in front of Gateway Elementary School in Woodland Park, Colorado.

schools to recruit and train teens as volunteer museum educators. The teens developed and presented interactive nature and science programming for children and adults visiting the museum.

schools to recruit and train teens as volunteer museum educators. The teens developed and presented interactive nature and science programming for children and adults visiting the museum.  Each year, the children’s museum receives hundreds of applications from teens for about 30 summer general volunteer positions such as ticket takers, gallery attendants and assistant educators.

Each year, the children’s museum receives hundreds of applications from teens for about 30 summer general volunteer positions such as ticket takers, gallery attendants and assistant educators. After an exciting two-week training process, the teen volunteers conducted daily workshops that had been planned by the museum’s education team. The first two workshops (in a series of 11) were done this way to allow time for staff to model programming techniques and lead the volunteers through the lesson planning process.

After an exciting two-week training process, the teen volunteers conducted daily workshops that had been planned by the museum’s education team. The first two workshops (in a series of 11) were done this way to allow time for staff to model programming techniques and lead the volunteers through the lesson planning process. The Green Teens led museum visitors in making crafts like grass heads, sun catchers, and model dragon flies. Students played hopscotch with their own handmade bean bags, made and raced origami boats, flew whirligigs, planted seeds, learned about birds, and decorated wooden animals.

The Green Teens led museum visitors in making crafts like grass heads, sun catchers, and model dragon flies. Students played hopscotch with their own handmade bean bags, made and raced origami boats, flew whirligigs, planted seeds, learned about birds, and decorated wooden animals.

Students performed better on tests after participating

Students performed better on tests after participating

Plans for the future

Plans for the future I was thrilled to receive a GreenWorks! grant from Project Learning Tree to help create a schoolyard habitat, part of an outdoor classroom at Valley Springs Elementary School in Arkansas. My third and fourth grade gifted and talented students designed and developed the project to provide food, water, cover and nesting areas to attract wildlife to their school grounds.

I was thrilled to receive a GreenWorks! grant from Project Learning Tree to help create a schoolyard habitat, part of an outdoor classroom at Valley Springs Elementary School in Arkansas. My third and fourth grade gifted and talented students designed and developed the project to provide food, water, cover and nesting areas to attract wildlife to their school grounds. If possible, visit a schoolyard habitat site or another project that’s similar to what you’ll undertake. Depending on the size and complexity of your project, it is important to have firsthand knowledge wherever possible.

If possible, visit a schoolyard habitat site or another project that’s similar to what you’ll undertake. Depending on the size and complexity of your project, it is important to have firsthand knowledge wherever possible. I formed a committee of teachers, students, school administrators, parents, and community partner volunteers to help implement this project. It truly was a community-wide effort.

I formed a committee of teachers, students, school administrators, parents, and community partner volunteers to help implement this project. It truly was a community-wide effort. Leslie works with Central High School’s environmental club, Nature’s Environmental Role Model (NERM). The thirty 10th-12th grade students that make up NERM had volunteered during the 2006-2007 school year at beach and roadside cleanups around St. Croix. Still, they wanted to take a more proactive role and become community leaders themselves. With the help of a Project Learning Tree (PLT) GreenWorks! grant, the NERM team organized a series of “Service Saturdays.” These community service days combined a litter clean-up with environmental activities and lessons from Project Learning Tree.

Leslie works with Central High School’s environmental club, Nature’s Environmental Role Model (NERM). The thirty 10th-12th grade students that make up NERM had volunteered during the 2006-2007 school year at beach and roadside cleanups around St. Croix. Still, they wanted to take a more proactive role and become community leaders themselves. With the help of a Project Learning Tree (PLT) GreenWorks! grant, the NERM team organized a series of “Service Saturdays.” These community service days combined a litter clean-up with environmental activities and lessons from Project Learning Tree.  Then, on a series of Saturday Service Days, NERM students conducted hands-on educational activities with other school-age students. The high school students led litter cleanups for the younger, elementary and middle school-aged participants. They also used the new trash bins and litter from trash clean-ups to demonstrate appropriate handling of different types of waste such as potentially hazardous materials, recyclable materials and oversized items.

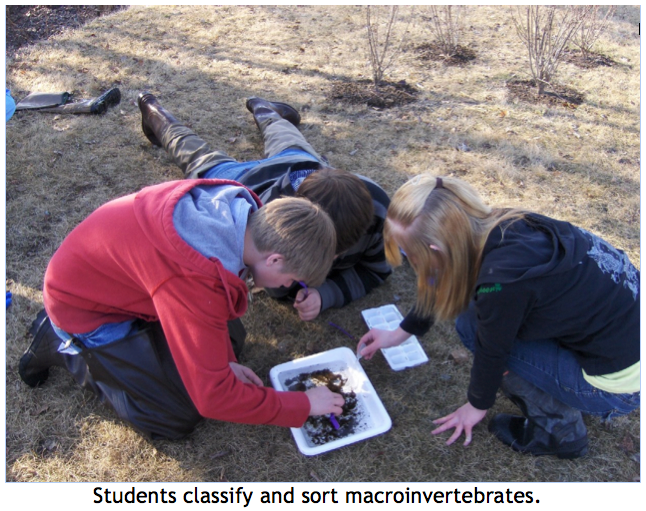

Then, on a series of Saturday Service Days, NERM students conducted hands-on educational activities with other school-age students. The high school students led litter cleanups for the younger, elementary and middle school-aged participants. They also used the new trash bins and litter from trash clean-ups to demonstrate appropriate handling of different types of waste such as potentially hazardous materials, recyclable materials and oversized items.  I’ve come a long way in my journey as a fifth grade teacher. I used to be stressed out about taking kids outside, but now I look forward to doing it every day. Along the way, my skills in instruction, classroom management, and curricular understanding have grown, and so have the projects themselves.

I’ve come a long way in my journey as a fifth grade teacher. I used to be stressed out about taking kids outside, but now I look forward to doing it every day. Along the way, my skills in instruction, classroom management, and curricular understanding have grown, and so have the projects themselves. Initially, most of my formal outdoor lessons were either from Project Learning Tree or Project WET. Much of the content was new to me, but these wonderful lessons are very well written, easily taught, and fun for the students. I implemented a “Buddy Program” to spread the learning to younger students at our school.

Initially, most of my formal outdoor lessons were either from Project Learning Tree or Project WET. Much of the content was new to me, but these wonderful lessons are very well written, easily taught, and fun for the students. I implemented a “Buddy Program” to spread the learning to younger students at our school. New Opportunities for Outdoor Experiences

New Opportunities for Outdoor Experiences