As any early childhood educator knows, young kids can accomplish great things.

At Country Day School (CDS) in McLean, Virginia, two-year-olds investigate how to reduce landfill waste and increase recycling. Three-year-olds focus on water quality and quantity. Four-year-olds map the school site, learn how to assess tree health, and conserve energy, while our oldest students, kindergarteners, research environmental quality.

As a play-based program that has been NAEYC-accredited since 1988, we already knew that nature-based activities help our kids in their social, emotional, and cognitive development. In 2019, we decided to engage in outdoor learning more effectively. However, we certainly did not expect that we would be heading into a year when we were outside in nature virtually 100 percent of the time! Or that our efforts would lead us to become the first early childhood certified PLT GreenSchool in the nation.

How It Started

CDS is fairly large, with about 220 children attending either part- or full-time, and about 35 teachers. When I surveyed teachers in early 2019, they requested professional development to take better advantage of our school grounds for learning. Our head of school, Diane Dunne, supported the idea as well. But where to start? Research into available programs led me to Project Learning Tree and the Virginia state coordinator, Page Hutchinson.

We lucked out, because Page was a strong advocate for early childhood activities within PLT. In August 2019, she came to Country Day to conduct a workshop on the PLT GreenSchools for Early Childhood program, and she continued to help us adapt the program to our school’s needs. For example, some of the investigations involve worksheets, which we do not use, so we collaborated on alternative options, such as interactive, hands-on activities.

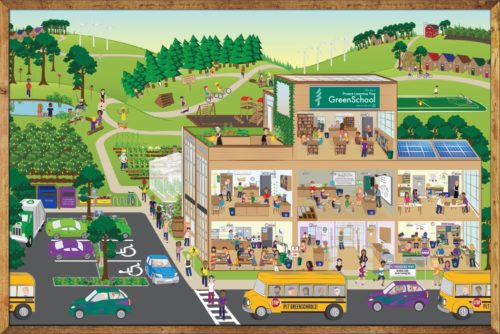

Our teaching teams reviewed the materials to decide which age group would focus on which of the PLT GreenSchool’s five main areas of investigation: Waste, Water, School Site, Energy, and Environmental Quality. Some ongoing activities could be used to fulfill GreenSchool requirements, and we also adapted or created others.

As one teacher commented, “CDS has always been a school that focuses on the outdoors and nature. The Project Learning Tree curriculum gave us some structure and new ideas for ways to deepen our study.”

How It Unrolled

How It Unrolled

We may have earned our PLT certification in any event, but a twist lay ahead—one that you are familiar with, I am sure. We dealt with COVID-19 by moving our classes outside on all but the most bad-weathered days. Cold weather, hot weather, rain—our kids were outside, dressed appropriately, with each class its own separate pod and all students and staff masked.

Fortunately, the school has many separate playgrounds and other outdoor areas, but it took a lot of planning and maneuvering to ensure that all remained safe. Parents could not volunteer or visit beyond drop-off and pick-up, so Cassandre Durocher, Director of Communications at Country Day School was busy sharing photographs and news with families about what we were doing.

Students and teachers rose to the challenge. We really looked at our outside areas with a new lens. We taped paper to tree trunks to become easels. Rocks held down smaller pieces of paper that might have blown away in the wind.

Another interesting development is that we needed to save money where we could, given the pandemic requirements of lower enrollment revenue and higher costs associated with new health measures. Old boxes became robots and vehicles, cut-up cardboard boxes became drawing sheets, and old pieces of fabric were stretched between trees for spray art. We not only saved heating and electricity costs by spending so much time outdoors, but the kids also learned first-hand the environmental and financial benefits of doing so.

By having each age level focus on one investigation area and taking advantage of many things the school already does, we fulfilled the requirements for PLT certification, which admittedly looked a bit daunting at first.

For example, every year, we have a garden event called the Big Dig. This year, thanks to the Water investigation, we focused on native plants. Similarly, we had a rain barrel that sat unused. The three-year-olds helped figure out where to move it to provide water for the troughs used for water play.

The company SavATree donated six trees; we also asked them to explain why the trees should be planted in particular spots on campus.

And when the waste and recycling trucks made their regular visits to pick up materials, the two-year-olds greeted them like celebrities!

As another example, the kindergarteners brainstormed how to improve air quality, given that virtually all the children arrive by private vehicle. They created signs to request families to turn off their cars at pick-up times to reduce air pollution. CDS has since created more permanent signs to communicate this message.

One day when I was doing carpool duty, one parent told this lesson particularly resonated with her son; she said, “On more than one occasion, I was greeted with a grimace, a grunt, and ‘Mommy! You forgot to turn off the car AGAIN!,’ followed by five minutes of him explaining how important turning off the car is to help make the air cleaner.” I think that’s a lesson that most parents would love their kids to learn.

How It Will Continue

As COVID-19 restrictions ease for the coming school year, we plan to be in our classrooms more often, but we laid the groundwork (pun intended!) to remain a PLT GreenSchool. Each age level will maintain its focus so that a child going through CDS will cycle through all five investigations.

After expanding the outdoor classroom for the pandemic school year and working with the 2-year-old classes to complete the waste and recycling investigation, one teacher was inspired to create a teachers’ committee to work on composting and gardening for the school.

Another commented that “as a ‘seasoned’ teacher, I always appreciate a curriculum that enhances my excitement about teaching young children, and this is something I can see using year after year.”

When we received the banner proclaiming our certification as a PLT GreenSchool, the kids, teachers, and parents alike were excited. I was sorry, however, that we could not share the news with Page Hutchinson, the PLT coordinator who was so supportive of our efforts.

Unfortunately, Page passed away suddenly in spring 2021. However, her advocacy of PLT for early childhood lives on at Country Day, and we hope we serve as an example, so there is at least one PLT Early Childhood GreenSchool in every state in the country.

Five Suggestions for PLT GreenSchool Success (at any age!)

- Take advantage of your state PLT coordinator and other PLT resources. They are there to make things easier for educators.

- Let teachers figure out how to divide up the investigations. They know what their students can handle, and they can also build on their own strengths (whether science, art, literature, or another subject) as a starting point.

- Ask teachers to document their activities as they go along, rather than wait until the end, then appoint one person to pull the pieces together for the PLT GreenSchool application form.

- Build on support from school leaders and parents. They can provide resources, encouragement, and ideas.

- Take advantage of events and activities already going on, such as community workdays, and of students’ excitement when they are outdoors.

Rain Barrels for Different Ages

Rain Barrels for Different Ages PLT Connections

PLT Connections One More Thing about Rain Barrels

One More Thing about Rain Barrels

Starting with Soil Science

Starting with Soil Science Community Collaboration

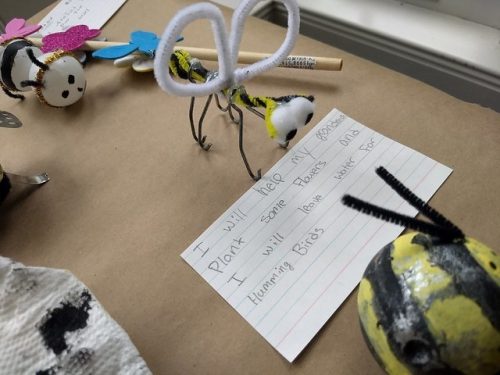

Community Collaboration Student Engagement and Impact

Student Engagement and Impact

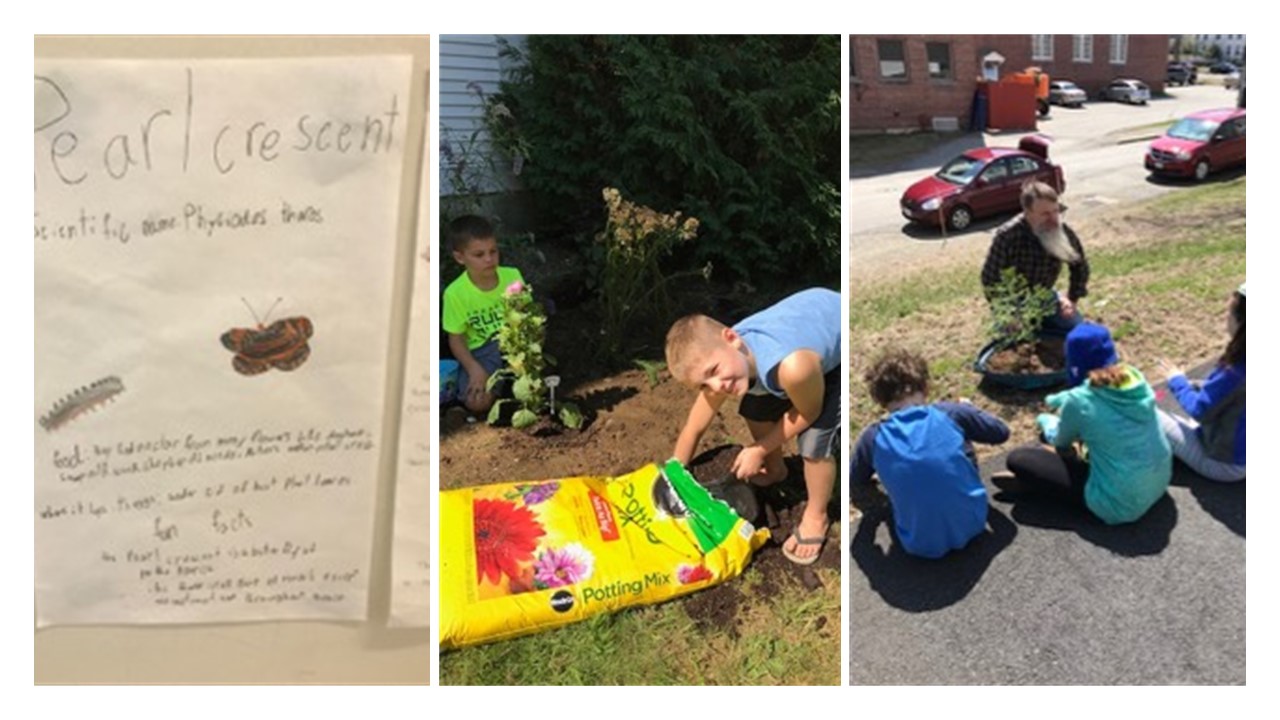

A community volunteer used his construction equipment to create the space. Members from the Sherburne Soil & Water Conservation Department and the Friends of Sherburne National Wildlife Refuge, along with teachers and parents, showed students how to plant and maintain the garden. Through the GreenWorks! grant and other donations, the garden also has bird houses and feeders, as well as picnic tables and benches.

A community volunteer used his construction equipment to create the space. Members from the Sherburne Soil & Water Conservation Department and the Friends of Sherburne National Wildlife Refuge, along with teachers and parents, showed students how to plant and maintain the garden. Through the GreenWorks! grant and other donations, the garden also has bird houses and feeders, as well as picnic tables and benches.